Often called the birthplace of wine, Georgia holds a winemaking history that stretches back 8,000 years. Scientists discovered traces of wine residue on ancient pottery shards, make it some of the earliest evidence of viniculture. Despite centuries of invasions and turmoil— like the whitewashing of cathedrals and the misuse of sacred wine vessels by Soviet forces— Georgia’s grapevines have remained strong. For generations, monks have served as the guardians of these ancient vines, tending to them with admirable devotion. One monastery, dating back to the 6th century, still holds grape-growing and winemaking as sacred act. During harvest season, monks walk through the vineyards, blessing the grapes and raising toasts in gratitude for the bounty. In Georgian tradition, wine wasn’t just a drink—it was divine. It was offered to the gods, believed to bring favor. Soldiers once tucked pieces of grapevine into their uniforms, believing that if they died in battle, a vine would grow from their heart. Though some grape varieties were lost in Georgia’s darker times…over 100 ancient varietals survive, with 40 still used in winemaking today.

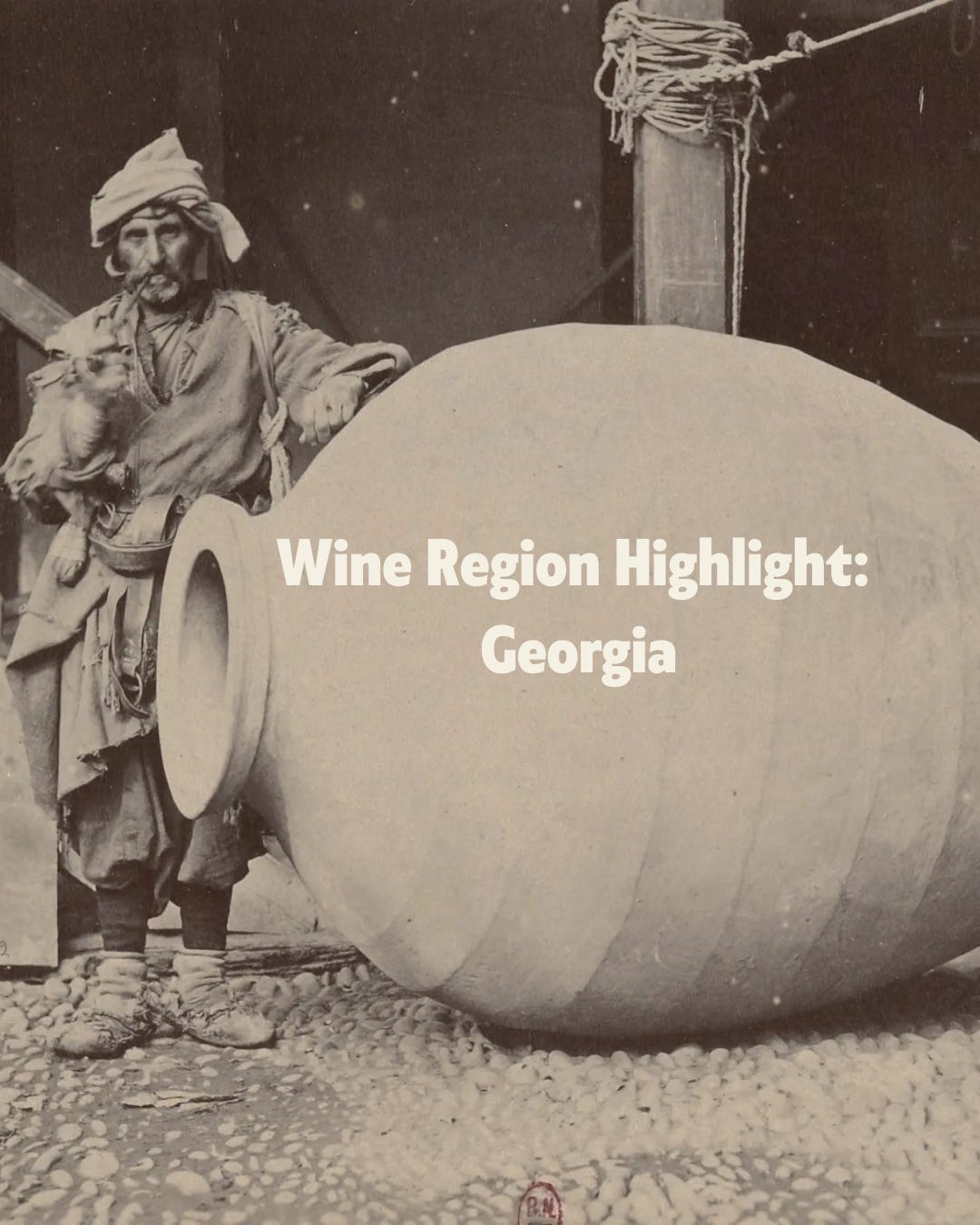

At the heart of Georgia’s unique winemaking tradition is the qvevri—massive clay vessels that are buried six feet underground, and used for fermenting and aging wine naturally. Some qvevris can hold up to 900 gallons, and only a few skilled artisans still handcraft them today. The wines that I’m sharing with you today are all made in a qvevri. I recommend pausing here and go to watch this perfect video (it’s only 2 mins!) illustrating how these wines are produced using this method. It’s one of the best ones I have found, at least for my learning style, when doing my research on Georgian wines the last few months. The grapes are harvested, crushed, and then all of the juice, skins, stems, seeds, and all are put into the qvevri. Once in the qvevri, they seal it with a coil of wet clay around the opening, and then a heavy stone is placed on top to ensure an airtight seal. This method helps to maintain the wine's temperature and prevent oxidation during the aging process. I find these wines so fascinating and enchanting, and so, in the least, I hope this inspires you to go try some Georgian qvevri amber wines. Especially if you a wino who loves a natural and skin contact wine. Impress your friends this summer by bringing one of the ancient natty skin contact wines!

Amber Qvevri Wines + Food Pairing

Amber wines have a full-bodied, savory profile with grippy tannins, thanks to the grape skins left intact during fermentation. These wines are a bit bolder than your typical white wines, with a texture reminiscent of red wines. Therefore we want to pair these wines with things have meet the same level of flavor punch. Savory flavors are the way to go here. Lots of spices, aged hard cheeses (Gruyère, Parmesan, Manchego), eggplant and other roasted vegetables, red meats, and nuts.

Andrias Gvino Mtsvane, Kakheti

100% Mtsvane | Kakheti, Georgia

This was my first sip of a Georgian wine. I can remember the experience clear as day. I was having a tasting at Village Vino in Kensington with a friend, and we both were so taken back (in the best way) over this wine. We had never heard of Georgian wine, nor had seen it on a menu yet in San Diego. It was the perfect summer Orange. Minerality, slightly grippy, loaded with melon, and a bit of almond that lingered on the palate afterward. To this day I regret not buying some bottles to take home because the wine shop owner was trying to sell them to make room for new bottles.. and this is when I knew I needed to do a deep dive on Georgian wine to get those bottles flying off the shelves because more people knew of a Georgian Amber!

Mtsvane (Mtsvani) means “Green” in Georgian and is name to about a half-dozen thinner/lighter-skinned grape native varieties. I find where I am (in San Diego) Mtsvane bottles are easier to source. Mtsvane (Mtsvani) makes crisp wine with citrus, pineapple like acidity, pear like tannin, and a floral aroma.

Andrias Gvino is a family owned and run winery, about 18.6 miles away from Georgia’s capital, Tbilisi. 100% natural wines, no additives or filtration.

Pheasant's Tears Tsitska 2021

100% Tsitska | Imereti, Georgia

Tsitska is part of the Imereti family of indigenous Georgian vines. The grape can be quite delicate on the aroma front, but improves greatly after maturing in barrels (or quevri). Tsitska is fresh on the palate with good balance, and once those aromas come through they can be of linden and a note of honey.

All of the wines produced at Pheasant’s Tears are aged in quevri. They state that since “all of {their} wines are aged exclusively in qvevri, no flavors are imparted from oak barrels. What some might consider a lack of oak {they} view as an opportunity to let the quality of the grapes and the resulting wine shine through.” Because Tsitska is a delicate grape, this wine has medium body, but with a prolonged amount of skin contact it becomes more grippy with tannins, like a pot of unsweetened black tea. Stone fruit, honey, and a tad vegetale. All of their wines are made from organically or biodynamically grown grapes with minimal intervention.

Ocho What Ru Waiting For? Kisi 2022

100% Kisi | Kakheti, Georgia

Kisi is an ancient grape that almost went extinct, but is having its revival. This is due to the phylloxera disaster of the late 19th and early 20th century. The grape is also extremely vulnerable to powdery mildew and black rot, and yields 25 to 30 percent less than it’s grape counterpart of the region: Rkatsiteli.

Ocho is the result of a passionate group of wine lovers and artisans coming together to bring new life to traditional Georgian winemaking. They're all about keeping things sustainable and organic, farming without synthetic chemicals and letting the grapes speak for themselves through minimal-intervention techniques. The name 'Ocho' reflects what they stand for—deep roots in the land, respect for heritage, and a strong sense of community."

Kortavebis Marani 2023 Selects Amber

95% Rkatsiteli, 5% Kisi | Kakheti, Georgia

Tamuna Bidzinashvili is the winemaker behind Kortavebis Marani. She began the vineyard in 2014, and now has 35 indigenous grape varieties growing. She practices organic and biodynamic farming practices, and all her wines are naturally produced. Rkatsiteli is one of Georgia’s most ancient and widespread varietal. It’s typically moderate to low acidity, so you often see it blended with other grape varieties to up the acidity. The grape has notes of pineapple, lime, resing, tarragon, and fennel. For this wine, the grapes were left on their skins for 1 month. This wine has crazzzy bodily grip to the palate.

Other recommendations or producers/places to know about:

Khachapuri (Coming soon to University Heights, San Diego soon!)

Recipe Pairing by Polina Chesnakova

I first discovered

when she worked at Seattle’s Cookbook shop: Book Larder. She was their culinary instructor, and had just released her first cookbook: Everyday Cake. It was at the same time last year that I started my deep dive into Georgian wines when I saw Polina was on a trip to Georgia with her family. Her Instagram posts, stories, and videos of lobiani, kveri dumplings, cucumber salads, breads, and cheeses, I immediately started planning my own trip to Georgia one day, and knew she would be the perfect person to be apart of this newsletter. Not only that, but Polina’s parents fled the fall of the Soviet Union in the Republic of Georgia when Polina was just a baby, so her roots run deep in Eastern Europe and the Caucasus. She even has a new cookbook you can pre-order now called Chesnok honoring these roots. You can follow her newsletter here on Substack (linked on her name above, or her IG: @ polina.chesnakova.Alright— now Polina will take it away:

Badrijani Nigvzit (Fried Eggplant Rolls with Spiced Walnuts)

Serves 6 to 8 as an appetizer, or about 24 rolls

You will find some variation of this dish on menus all over Georgia—and for good reason. Planks of eggplant turn silky and unctuous after a pan-fry; then get slathered in a spiced walnut paste before being rolled up. Tart pomegranate seeds, while not always in season, help cut through the richness and add a beautiful pop of flavor (a little drizzle of pomegranate molasses over the top could also work!). To eat, pick one up with a fork, smash it onto some good crusty flatbread, and dig in. Washed down with a good amber wine, you’ve just experienced one of my all-time favorite bites.

Notes: When picking out eggplant, if “globe” isn’t available, look for varieties that are on the longer side, such as Japanese or Chinese, which will be more suitable for rolling.

You want your paste a little looser than you think because the walnuts will hydrate overtime; if there’s not enough liquid, the filling will be a bit dry (for that reason, sometimes my mom adds a bit of mayo to help emulsify things). Also, the recipe makes a lot of paste because I’d rather have more than not enough to fill all the rolls. Use any remaining as a spread or dip, or a sauce to go with chicken or fish.

As for the spices, my favorite purveyor of Georgian spices is Suneli Valley. They work with farmers in Georgia to source and blend super fresh spices and herbs to import them to the US. Also available on Amazon!

Ingredients

2 large globe eggplant (3 to 3 ½ lbs), destemmed, partially peeled in alternating stripes, cut lengthwise into ¼ to ⅓ -inch (6.5 mm to 8.5 mm) planks

DC kosher salt

¼ cup (55 g) sunflower oil or other high-smoking point oil, plus more as needed

Pomegranate seeds, to garnish

Filling:

1 ½ c (170 grams) walnuts

½ large bunch fresh cilantro, leaves and tender stems, roughly chopped

3 large garlic cloves

2 ½ teaspoons DC kosher salt, plus more to taste

1 ½ teaspoon ground marigold

1 ½ teaspoon ground blue fenugreek

¼ teaspoon cayenne, plus more to taste

⅔ cup (155 g) water, plus more if needed

1 tablespoon red wine vinegar, plus more to taste

2 tablespoons mayonnaise (optional)

Instructions

Sprinkle each eggplant plank with a small pinch of salt on both sides and transfer to a colander set over a bowl. Let stand for at least 30 minutes while you make the filling.

In a food processor, blitz the walnuts, cilantro, garlic, salt, and spices until finely ground. Add the water, vinegar, and mayonnaise (if using) and process until thoroughly combined. You want the paste to be the consistency of a loose pesto, so if needed, add another tablespoon or two until desired consistency is reached. Taste and season with more salt or vinegar if needed until filling is bright and sharp. Set aside.

Working in batches, stack 4 to 5 eggplant slices on top of each other and use your hands to squeeze any excess liquid. Pat each slice dry.

In a large non-stick skillet, heat oil over medium heat until shimmering. Working in batches, fry the eggplant slices until lightly browned on the bottom, 3 to 4 minutes. Lower heat if needed if eggplant is browning too quickly. Use a fork to pierce the base of the eggplant and flip. Cook until the bottom is lightly browned and the eggplant is fork-tender, another 2 to 3 minutes. As they are done, pick up the eggplant slices with the fork, shake over the pan to remove any excess oil, and transfer to a paper towel-lined plate. Repeat with the remaining slices, adding oil as needed.

While the fried eggplant slices are still warm, spread each slice generously with the filling and roll up starting from the base. Transfer rolls seam-side down to a serving platter or storage container. Serve at room temperature, garnished with pomegranate seeds, and bread on the side. Refrigerated, the badrijani will last for up to 4 to 5 days.